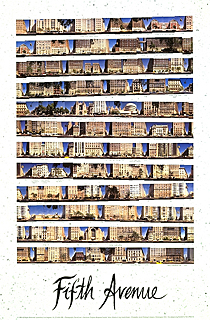

Fifth Avenue

Poster by

David Yost

Booklet by

Steve Marvin

This is the Web edtion of the booklet

that accompanies the Fifth Avenue poster.

Contents

The Making of the Poster

Pictures alone don't tell the whole story. I wanted you to enjoy something of the architectural and social history behind the buildings as you take an imaginary stroll down the Avenue on the poster, so I asked my friend Steve Marvin to write this booklet. There is also a story behind the making of the poster, which I will recount here.

The Fifth Avenue poster started out as an idea that came to me one morning on a visit to New York, where I had lived for a while in my twenties. Although I now live in Los Angeles [1987], I am still susceptible to the excitement and grandeur of New York, so I often go back.

The idea was to capture the majestic façade of Fifth Avenue facing Central Park in a single, long, linear panoramic photograph. I briefly considered using a panoramic camera mounted on a moving car. (A panoramic camera moves a roll of film continuously past a narrow slit just in front of the film and is usually used for circular panoramas.) I discovered that panoramic photographer Ron Globus had tried such an experiment, so I went to see how it turned out. The perspective in the photograph was very flat and strange (the side streets went straight up with no perspective narrowing toward the horizon, and you couldn't see the sides of the buildings), and the photo had a waviness caused by the inevitable camera unsteadiness in a moving vehicle. Clearly this approach was not the way to go.

So, I settled on the more straightforward approach of taking individual photographs and making a continuous montage. Photographing tall buildings from across the street calls for a very wide angle lens. Yet the distortion typical of many wide angle lenses would bend the parallel vertical lines in the image, ruining any attempt to join the photos side-by-side into a continuous montage. [In 1997, you can now do this. You tilt the camera up as necessary, then undo the perspective distortion in graphics manipulation software such as Photoshop.] Luckily, there existed an extremely wide angle distortion-free lens fit for the job: the amazing Nikon 15 mm rectilinear wide-angle lens for 35 mm film. It weighs a half pound, measures 3 1/2 inches in diameter, and has a bulging-glass shape usually associated with a fish-eye lens. (Nikon also makes an even more amazing 13 mm rectilinear wide-angle lens, but that seemed like overkill.) I pointed the camera lens exactly horizontal and perpendicular to the building façades, taking special care to keep the vertical lines parallel on the film so the montage would work. The lens yielded photos reaching 50 degrees up from horizontal to an approximate height of 100 feet on the closest buildings, surpassing the angle of view of the widest-angle “perspective-correcting” or “shift” lenses available.

To ensure a maximum of unobstructed sunlight on the buildings, I took the photographs around the time of the summer solstice. In 1983, the year I took the photos, there was an incredible, sustained spell of absolutely crystal clear weather for five days starting June 21. What luck! Weather like that comes once in ten years. But would I be able to get all the photos before the weather changed? There were only two and a half hours for shooting: from 2:45, when the sun was far enough out in front of the buildings, to 5:15, when the sun went too low, casting shadows on some of the buildings and reflecting in some of the windows. I would have to work very fast.

I had to avoid wasting a lot of time leveling the tripod and aligning the camera, important though it was to aim the lens exactly perpendicular to the buildings. The answer was to put two heads on the tripod, one on top of the other. Instead of leveling the tripod, I quickly leveled the lower head which had a bubble level on it. The lower head now acted as a level platform for the upper head which held the camera perfectly horizontal, so it was easy to turn it left and right until the buildings were properly lined up with the hairlines on the ground glass.

For each photo, I planted the tripod, lined up the camera to the buildings, took a shot or two, then trotted to the next position with the camera on the open tripod, averaging one shot every two minutes. The traffic came in waves, so it was usually not hard to get shots free of passing cars. Parked tour buses on the camera side of the street were a worry, but all the drivers (including one I had to wake up) were kind enough to move their buses for me.

Now there was the problem of how to produce a high-quality poster from 214 Kodachrome-25 slides. Enter modern computer graphics technology. Scitex Corp., world renowned makers of color separation equipment for the printing industry, agreed to collaborate on the project. Their “Response” system, a computer system for use in page preparation for color printing, allowed us to scan the color photographs into the computer as digital data. Since the system is digital, the images perfectly retained their clarity and color all the way through the process from montaging, layout, and retouching, to exposing the film used in making the plates for the printing press. A more conventional approach would have required intermediate film copies, with a significant loss in picture quality.

I carefully aligned and mounted the slides on acetate, twenty to a sheet, to make the scanning go quickly. Members of the Scitex demo center staff scanned in the transparencies on their Dainippon laser scanner, then Gayle Rosen cropped and positioned them interactively on the color video workstation of the Response System.

The montaging went like this: Gayle brought up a photo on the screen, then indicated the vertical crop line on the right of the photo where the next photo was to connect with it. (In most cases this seam was not a straight vertical line but a series of connecting lines that followed the details of a building.) Then she brought up the next photo on the screen to the right of the first one and slid it around “under” the overlapping, cropped right edge of the first photo until it was where she wanted it. Once she had positioned the new photo, she slid the whole strip to the left on the screen and repeated the process for the next photo. At any point in the process she was able to easily enlarge or reduce the image on the screen to facilitate working on detail or viewing the overall effect.

The multiple camera positions used to make a continuous linear photo montage result in some interesting side effects, as you can see on the poster: two different cars are sometimes joined on adjacent photographs, and in some places, the same background building appears in as many as four adjacent photographs. We came to like these curious artifacts, and decided not to worry about trying to retouch them out. The stair-stepped irregularity of the strips is a direct result of the fact that Fifth Avenue is not level; the montage shows all of the Avenue's ups and downs. In several places, the choice of cut points was tricky because of trees hanging down into the photos. The most difficult building to put together without trees was The Museum of the City of New York, which is made up of five shots, one of which is used only for the portico. The most satisfying montage was the Guggenheim because it presents a relatively undistorted full portrait which is impossible to get as a single shot.

After the montaging was complete, we took magnetic tapes of the digital image data to Acme Printers. They read the data into their Scitex equipment, did some final color correction, and then output screened color separation films of the montage strips. These were used along with the films of the lettering and the background texture to make the plates and print the poster as you see it.

If the poster gives you a sense of being there on the Avenue on a brilliant summer day, I will be happy.

David Yost

September 19, 1988

Millionaire's Row

Fifth Avenue Facing Central Park

This fabulous piece of New York City real estate, two-and-a-half miles long and a few hundred feet wide, bordering the east side of Central Park from Grand Army Plaza at 59th Street to Frawley Circle at 110th, has been for about a hundred years one of the prime residential areas in the world. Soon after the opening of Central Park in 1876, it became the home address mecca for New York's wealthiest families.

Why did it win out over other geographical sections of the city? The answers are simple: beautiful Riverside Drive, overlooking the Hudson River, was simply too far away from the center; Central Park West, although similarly adjacent to the Park was on the wrong side of town; and Park Avenue, despite its name, lacked the Park--besides being on the wrong side of the tracks until they were covered over in 1913. By that time, upper Fifth Avenue had become the city's Gold Coast. To quote James Theodore, Jr.: “It is quite probable that the world had never seen nor will ever see again such a concentration of wealth as that represented by the mansions that were built on upper Fifth Avenue from 1890 until World War I. Millionaires' residences stretched for a solid mile and a half from 59th Street to 90th. ... Nearly seventy mansions facing Central Park housed treasures assembled from the four corners of the earth.”

The magic ingredients of appeal for this particular locale were two: its convenience of location relative to the center, and the Park. The presence of the latter meant little or no crosstown traffic, a broad tree-lined boulevard for up- and downtown traffic, wide sidewalks on either side for promenading, and no houses across the Avenue, only greenery and more greenery.

By 1910, Millionaires' Row was in place, a nearly unbroken line of palaces, castles, and chateaux, eclectic mansions from the drawing boards of the city's foremost architects: Richard Morris Hunt, Warren & Wetmore, Delano & Aldrich, C. P. H. Gilbert, Carrère & Hastings, McKim, Mead & White, and many more.

Since the opening of the Park, this section of Fifth Avenue has undergone three distinct waves of building, predominantly residential in nature. The first wave saw the construction of often ornate, individual town houses, one per lot. The second wave took the form of large neo-Renaissance apartment houses, usually twelve to fifteen stories, whose start can be pinpointed at 1910 with the construction of 998 Fifth Avenue (at 81st Street) by McKim, Mead & White. The economic factors involved in this shift from town house to apartment house were a sharp rise in the city's population, an increase in real estate taxes, and a change in zoning regulations that allowed buildings to go up as high as twelve stories. As can be seen at 998 Fifth Avenue, this new kind of dwelling took the agreeable form of a neo-Renaissance Italianate palazzo, blown up in size and height, but kept carefully in scale. Nearly half of the apartment buildings erected between 1915 and the early 1930s were the work of two outstanding architects: J. E. R. Carpenter and Rosario Candela. Between them they set the tone for all the “tenement houses,” as they were called, to follow. And the new buildings offered a novel style of living that soon proved irresistibly popular among the former householders.

In effect, what happened during the second wave was that where once stood two or three private, attached mansions, there now rose a limestone box containing the equivalent of several such houses on the same piece of land, stacked one atop the other, one spacious apartment per floor, and in some cases, one apartment per two floors. If Fifth Avenue sites were to be provided for these new multiple dwellings, it meant that a great many of the first-wave town houses would have to be demolished. The astonishing thing is that the dispossessed former homeowners did not abdicate and migrate elsewhere; on the contrary: A great many of them became the first tenants in the new buildings. Still charmed by the geographical amenities of the locale, they simply converted from living in private houses to living in apartments. In 1915, near the start of this period of conversion, some ninety percent of Fifth Avenue's wealthy occupied their own private mansions and town houses; twenty-five years later, ninety percent lived in apartment houses. And the apartment houses designed and built for them during this period were so superior in terms of taste, opulence, efficiency, and comfort that they not only attracted the affluent tenants of their own era, but steadily appealed to later generations, thus surviving in great numbers down to the present. The second wave of construction tapered off in the early 1930s, and little new building ensued during the Depression and the pre-World War II period. As a consequence, upper Fifth Avenue is noticeably lacking in examples of the Art Deco style of architecture so prevalent along Central Park West and on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx.

In the thirty-five years since World War II, the third wave of building has been marked by the construction of high-rises and a severe falling-off in taste and distinction of design, perhaps epitomized by the apartment house erected at 900 Fifth Avenue in 1958. Because most high-rises of this period were sited at the expense of still-surviving first-wave town houses, one regrets that no Landmarks Preservation Commission was in force to stem the tide. The chief architectural firms active during these lean third-wave years have been Emery Roth & Sons (who bridged the gap from the late 1920s to the 1950s), Sylvan & Robert Bien, and Wechsler & Schimenti.

Lining the east side of the upper portion of Fifth Avenue today stand 119 structures: of them, twenty-seven are from the first wave, the Gilded Age town-house period; sixty-five are from the second wave, the apartment house era; and another twenty-seven are from the third wave, the high-rise postwar years. The great majority are the neo-Renaissance, mostly masonry apartment houses of the second wave, and it is these that create the present-day texture and flavor of the architectural fabric of this wonderful area. Their survival and continued occupation have kept the Avenue overwhelmingly residential. Still opulent and luxurious inside, masterful in scale and tastefully ornamented outside, these great stone vessels are interspersed with a few glorious remaining town houses (now mostly museums or other institutions) and thankfully few latter-day high-rises. We must feel fortunate indeed that the toll has not been greater, and that so much that is fine has come down to us largely intact and still very much in use.

Museum Mile

The upper stretch of what has been called Millionaires' Row has in recent years become known as Museum Mile. Lorded over on the west by the sprawling Metropolitan Museum of Art (entrance at 82nd Street), a neoclassical doyen indeed with splashing fountains and cascading steps, the other members of the Museum Mile are:

| 82nd | Goethe House |

| 85th | Yivo Institute for Jewish Research |

| 88th | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum |

| 89th | National Academy of Design |

| 90th | Cooper-Hewitt Museum |

| 92nd | Jewish Museum |

| 94th | International Center of Photography |

| 103rd | Museum of the City of New York |

| 104th | El Museo del Barrio |

These fine institutions offer the general public a rich concentration of museums, galleries, reference libraries, and archives. At certain times of the year, motor traffic is blocked off from this section of the Avenue, and a cultural sort of pedestrians-only street fair takes place.

Notes

Historic Districts

The Landmarks Preservation Commission has designated three historic districts that cover portions of Fifth Avenue on Central Park:

Upper East Side

Metropolitan Museum

Carnegie Hill

Scaffolding

When the photographs were taken, the City had just had a rash of incidents of pieces of masonry falling from tall buildings. To rectify this, the City ordered landlords to correct these defects and to protect pedestrians meanwhile by erecting sidewalk scaffolding.

About the Author

Born in 1915, Steve Marvin (Princeton, US Navy) was a resident of New York City all his life, first on Manhattan's East side and subsequently in Brooklyn Heights. Throughout those years he was an enthusiastic scholar of the city's history and architecture. Steve was a radio producer for NBC for many years and was a pioneer producer in the very early years of television. In the early 50s he produced “The Voice of Firestone” on TV, and in the 70s he produced for Monmouth Evergreen Records. Charles Steven Marvin passed away in 1995 at age 79 shortly after moving away from Brooklyn Heights, where he had lived since the 1960s. Video clips featuring Steve are here., or click on his portraait:

The Buildings

59th

781 - Sherry-Netherland Hotel - Schultze & Weaver, 1927

This architectural firm specialized in posh hotels: They did the nearby Pierre, the Waldorf-Astoria, the Los Angeles Biltmore, and the Breakers in Palm Beach. The Sherry-Netherland is one of their most exquisite. Behind the handsome travertine base (the poster photographs show the start of a cleaning operation) lie the small elegant lobby, a restaurant, and the fashionable antique shop, A La Vieille Russie (separate entrance on Fifth Avenue). On the sidewalk out front is a rare surviving piece of street furniture: a free-standing pedestal clock.

785 - Apartment House - Emery Roth & Sons, 1962

60th

1 E. 60 - Metropolitan Club - McKim, Mead & White, 1892

Founded by J. P. Morgan in a fit of pique because a candidate he had proposed for membership in the Union Club was blackballed. He summoned Stanford White and said, “Build a Club fit for gentlemen. Damn the expense.” And so it was that on land formerly owned by the Duchess of Marlborough rose this exuberant neo-Florentine palazzo. Besides the Metropolitan Club, little of this prestigious firm's upper Fifth Avenue work survives (see 972, 973, 998). Elsewhere, among the many splendid public buildings they created were the first Madison Square Garden, the Morgan Library, and the original Penn Station.

795 - The Pierre - Schultze & Weaver, 1928

The Pierre's reputation for being a stylish hotel is, as can be seen, well-urned. The clean, French neoclassical manner is topped by a verdigris “stretch” mansard roof. On this site formerly stood Richard M. Hunt's splendid mansion for Elbridge T. Gerry, a member of long standing in New York's “Four Hundred.”

61st

800 - Apartment House - Ulrich Franzen & Assocs., 1978

The street line false front designed to mask the high-rise behind caused great controversy. Actually, it is more like a masonry-clad narthex and thus really part of the main building--and largely successful. By its reasonable height it takes the pressure off its neighbor to the north (the Knickerbocker Club), ties in nicely with the Pierre to the south, and holds the street line very effectively while lessening the impact of the massive yellow brick tower lurking behind and above. For many years this spacious lot contained nothing but the undistinguished, seldom used, and all but abandoned pseudo-Georgian town house of Mrs. M. Hartley Dodge, the former Geraldine Rockefeller, daughter of John D.'s brother William, who was married to the founder of the Remington Arms Company.

2 E. 62nd - The Knickerbocker Club - Delano & Aldrich, 1914

The architects combined their two specialties in this engaging red brick building: the private social club (the Colony, the Union) and the neo-Georgian style (1130 Fifth, and the former Baker house at Park and 93rd). As a club it is one of the last bastions of old New York society; as a building it's a beaut, with fine proportions and elegant marble trim from basement to roof balustrade.

62nd

810 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

Our first example of this influential architect's fine handiwork. Between 1916 and 1929 he designed sixteen of these limestone apartment buildings for upper Fifth Avenue, varying in shape and size, but all fundamentally in the Italianate neo-Renaissance mode, with or without rustication or quoining, but always with subdued, tasteful ornamental touches. Many of them displaced private mansions--in this case, that of Hamilton Fish, who promptly became the new apartment building's first tenant.

812 - Apartment House - R. L. Bien, 1962

A sampling of what happened in the post-World War II years. And part of the price was the loss of the Jules S. Bache residence at 814, which contained his small but excellent painting collection, opened to the public in 1937 and later bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum when 814 was razed.

815 - Town House - c. 1870; redone Daub & Daub, 1953

Remarkable only for having survived, this is one of the Avenue's oldest private houses and the only one in brownstone. Today it contains apartments and a dentist's office.

817 - Apartment House - Starrett & Van Vleck, 1916

This invitingly opulent building, along with its near-twin, 820, represents the earliest and most successful adaptation of the Italian Renaissance vocabulary to the expanded proportions of a New York apartment house. Together they were the only Fifth Avenue residential work by these fine architects, whose other buildings include Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale's, Lord & Taylor, and the late, lamented Abercrombie & Fitch.

63rd

820 - Apartment House - Starrett & Van Vleck, 1916

This equally splendid Starrett & Van Vleck apartment building was renowned in the 1920s as the residence of Governor Alfred E. Smith.

825 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1926

By the time this went up, the twelve-story lid was off the zoning laws. These twenty-three stories were built by a developer who called for five apartments per floor instead of one. The lower façade is unusually ornate for Carpenter, while the 2 upper façade is of brick instead of stone. The red-tiled hipped roof stands out in the skyline.

828 - Town House - N. C. Mellon, 1896

Originally the home of coal mine owner Edward J. Berwind (who also built “The Elms” at Newport), this handsome red brick and limestone neo-Romanesque mansion is a sturdy survivor from the days when the region was Millionaires' Row. Occupied for a time by the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences, it is now split up into apartments. Note the stone and verdigris railing enclosing the moat.

64th

834 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1930

Our first meeting with the fine Italian hand of Signor Candela--and it's one of his masterpieces. His style was close to that of Carpenter (see 810) but always a bit more ornate, a little classier. He built nine apartment houses such as this on upper Fifth, as well as others on Madison and Park, but this huge one was probably his most successful. Each interior floor was left unfinished so that the tenant could lay it out as desired. The exterior ornament is rich with just a hint of Art Deco.

838 - Union of American Hebrew Congregations - Harry M. Prince, 1950

An unassuming office building whose simple neo-Romanesque style also relates nicely to its surroundings and blends well with 834. A pleasant touch is the peach marble used in the window spandrels.

65th

1 E. 65th - Temple Emanu-El - Kohn, Butler & Stein, with Mayers, Murray & Philip, 1928

Here stood the mansion of the Mrs. Astor (Caroline Schermerhorn Astor), built after she left 34th Street. Alongside was that of her son, John Jacob Astor. Both came tumbling down to make way for this massive Art Deco, Byzantine-Romanesque structure of somewhat cold and forbidding character. The side walls, running parallel east-west, are some of the largest load-bearing masonry walls extant; they support huge transverse steel beams.

845 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1919

One of his earliest--and best.

The apartments, one per floor, have eighteen rooms, six baths, and twelve-foot ceilings. Their decorative details are largely intact.

66th

850-3 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1949

Candela died in 1953, so he probably was not intimately involved in the design of this building. And yet the luxurious appointments bespeak his style and taste.

854 - Town House (Yugoslav Mission to the U. N.) - Warren & Wetmore, 1905

Originally built as the residence of R. Livingstone Beekman by Warren & Wetmore (whose stunning earlier work included Grand Central Terminal as well as the New York Yacht Club on West 44th Street), this two-bay wide Beaux-Arts mansion is one of the Avenue's finest surviving small town houses. Extended to ten or twelve bays it would make a charming palace.

855 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1928

A generously proportioned, expanded version of a fifteenth-century Italian palazzo, done with Candela's sure touch. The gray limestone is severely plain, yet pleasing.

67th

857 - Apartment House - R. L. Bien, 1963

Once the site of railroad tycoon Jay Gould's town house, it was later that of a Horace Trumbauer mansion for Countess Széchenyi, daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II and inheritor of “The Breakers” at Newport.

860 - Apartment House - S. L. Bien, 1949

Earlier and a good deal larger than 857, but basically more of the same--where once rose the stately home of Thomas Fortune Ryan, a Catholic financier from Baltimore who made money in whatever he touched: utilities, transportation, tobacco.

68th

870 - Apartment House - William I. Hohauser, 1948

An exemplar of post-World War II construction, it replaced the first-wave mansion built by William C. Whitney, originally at 871 and inherited by his older son, Harry Payne Whitney, who married Gertrude Vanderbilt, the famous sculptor and founder of the Whitney Museum.

875 - Apartment House - Emery Roth & Sons, 1939

See 880.

69th

880 - Apartment House - Emery Roth & Sons, 1947

Although built eight years later, this building is virtually the twin of 875. The first demolished Richard M. Hunt's town house for Ogden Miller, while the second mowed down a whole row belonging to the likes of E. H. Harriman, Adolph Lewissohn, Mrs. Oliver Gould, et al.

884 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1927

What a relief after the preceding pair! And what a difference twenty years (backwards) make. These fourteen stories sit on a rusticated basement and mezzanine, and form a fitting background for the nearby Frick.

70th

1 E. 70th - Mansion (The Frick Collection) - Carrère & Hastings, 1914”

This was one of the last of the first-wave private mansions to be built before the shift to apartments took sway. The firm of Carrère & Hastings had already done the magnificent Beaux-Arts New York Public Library at 42nd Street (1911) when Henry Clay Frick, a coke and steel industrialist from Pittsburgh, partner and bosom millionaire of Andrew Carnegie, commissioned them to create this architectural masterpiece: a lavish private residence designed for eventual conversion to a public museum. Building on the former site of the Lenox Library, just incorporated into the new Public Library, they fulfilled the assignment in handsome Louis XVI style; the charming façade occupies the entire block front on the Avenue and is set off by a side pavilion, a raised lawn, balustrades, and magnolia trees. The conversion to the present museum took place under the loving hands of John Russell Pope from 1931 until the official museum opening in 1935. The superb Frick Collection of painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts well warrants such superior housing.

71st

900 - Apartment House - S. L. & R. L. Bien, 1958

This white brick and pseudo-glass-wall high-rise, at odds with its neighbors, lies between two of upper Fifth Avenue's most delightful survivors: the Frick mansion and the apartment house at 905-907. It did away with two fine mansions to boot: Florence Vanderbilt Twombly's rather dour chateau by Warren & Wetmore on the corner, and Mrs. Elinor Widener's house by Horace Trumbauer to the north.

905-907 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1915

Awarded the A.I.A. Gold Medal in 1916, this early and solid building is perhaps Carpenter's best. The horizontal string courses, the rustication of the lower floors, the fine ornamentation, and the pronounced cornice all combine to make this massive structure pleasing and most distinguished. There were no more than two apartments per floor in 1915; the largest had twenty-eight rooms and rented for $30,000 a year. Huguette Clark's pad was the entire 12th floor.

72nd

910 - Apartment House - Fred F. French, 1919; renovated S. L. & R. L. Bien, 1959

Instead of the classic instance of town house disappearing to make way for the apartment house, here a fine neo-Renaissance apartment house was stripped to its steel frame--and reborn as a high-rise in white brick.

912 - Apartment House - Schwartz & Gross, 1925

920 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1921

73rd

923 - Apartment House - S. L. Bien, 1950

925 - Town House - C. P. H. Gilbert, 1898

926 - Town House - C. P. H. Gilbert, 1898

This pair of beige brick survivors from the first wave are fraternal twins. Vaguely neo-Romanesque but of less than mansion rank, they would be more at home on a side street. While still retaining their stoop, they have been split up into individual apartments.

927 - Apartment House - Warren & Wetmore, 1917

A fine sample of a second-wave apartment house by a firm not usually engaged in residential work (see 854). Noticeable is the grand arched entry with head-scroll keystone.

74th

930 - Apartment House - Emery Roth & Sons, 1939

Good, straightforward work by this legendary, chameleon-like firm that was responsible for so many good late-1930s apartment houses, both here and on Central Park West. Later, in the 1940s and 1950s, they went in for pseudo-International style glass-box office buildings, squeezing out the ultimate interior square footage, to the developers' delight.

934 - Town House (Consulate General of France) - Walker & Gillette, 1926

This versatile firm could work in almost any style, and do it well. If they favored any one in particular, it was the neoclassical Beaux Arts, as here in this late bloomer of a town house. The all-over rustication and the monumental entrance directly off the sidewalk seem a bit self-conscious and mannered.

936 - Apartment House - H. J. Harman, 1954

75th

1 E. 75th - Mansion (Commonwealth Fund) - Hale & Rogers, 1908

Built for Edward S. Harkness, this is one of upper Fifth Avenue's brightest jewels. Harkness was one of six original partners in Standard Oil; the Rogers of Hale & Rogers was James Gamble Rogers who understandably became Harkness's favorite architect, and went on to do wonders for him on the Yale campus at New Haven. Here on Fifth Avenue he created for his patron an exquisite neoclassical palace of delicate proportion and detail that has come down to us scrupulously intact, inside and out. Note the handsome tall wrought-iron fence that surrounds it on two sides.

944 - Apartment House - N. Korn, 1925

Similar in style to Carpenter's work, featuring fine Renaissance ornament, especially the two-story pilasters. The same little-known architect also designed 956.

945 - Apartment House - Emery Roth & Sons, 1948

Late for them still to be doing this kind of work. The white granite façade, with its center balconies, is well integrated for a late-1940s creation.

76th

950 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1926

Slim, simple, and tasteful; the corner pilasters shoot right up nine stories to the cornice.

952 - Apartment House - H. O. Chapman, 1923

953 - Apartment House - J. N. Philip Stokes, 1925

On the narrow site of a single town house, the architect erected the equivalent of six.

955 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1937

One of the great ones. The nearly astylar façade has a pleasant ripple-effect facing applied from the second to fifth floors.

956 - Apartment House - N. Korn, 1924

A distinguished façade that adds immeasurably to the overall fabric of the Avenue.

NOTE: This is the only block on upper Fifth Avenue to embrace as many as five separate building façades.

77th

960 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela with Warren & Wetmore, 1929

In 1904 on this site, Lord, Hewlett & Hull built an extravaganza of a town house for Senator William A. Clark, the copper king from Montana. Said to have been the most outlandishly ornate mansion ever built in New York, it took six years to construct, yet fell victim to the wrecker's ball only twenty-five years later. This successor apartment house is very large (ten by fourteen bays), and it should be noted that the façade's window arrangement is asymmetrical--a result of each original apartment owner having been allowed to have his unit laid out to his own specifications.

965 - Apartment House - Irving Margon, 1939

This building occupies the site of the Jacob H. Schiff mansion. The architect had earlier (1929) designed the Eldorado, the splendid twin-towered Art Deco apartment house at Central Park West and 90th Street.

969 - Apartment House - J. L. Raimist, 1925

78th

1 E. 78th - Mansion (New York University Institute of Fine Arts) - Horace Trumbauer, 1912

Built to be the residence of the grand Duke: James B., president of American Tobacco and father of Doris. This exquisite mansion in Louis XV style is of a smooth limestone so fine it looks like marble. The architect, Philadelphian Horace Trumbauer, based it roughly on the Hotel Labbatière, a late eighteenth-century chateau in Bordeaux. In 1959, Doris Duke gave the building to NYU, who hired Robert Venturi (also from Philadelphia) to remodel the interior, which he did with respect.

972 - Town House (French Embassy - Cultural & Press Services) - McKim, Mead & White, 1905

This smashing semi-attached town house was built by Stanford White for Payne Whitney, younger brother of Harry Payne Whitney (see 870). Happily, the French government bought it, and they have maintained all its inner and outer splendor. The handsome bow-front façade is of white granite, a strangely hard-to-work stone to choose, considering the intricacy and delicacy of the ornament.

973 - Town House - McKim, Mead & White, 1906

Although it seems to be part of 972 (cornice, moldings, and rustication all match perfectly and mesh horizontally), it is actually a separate house, built for the J. C. Lyons Co., which sold it on completion to Henry Cook, who left it to his daughter, the Countess de Heredia. Long the property of the Mormon Church, it is today occupied by a single private owner. The startling similarity between these two buildings is explained by the fact that they had the same begetter: Stanford White.

2 E. 79th - Mansion (Ukranian Institute of America) - C. P. H. Gilbert, 1899

Originally built for Isaac Fletcher, this house is best known as the Augustus van Horn Stuyvesant mansion; he was the last direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, and after spending his final years here as a virtual recluse, died in 1953 and was buried along with his forebear at St. Mark's-in-the-Bowery. The mansion is an integral part of the last complete block of town houses remaining on upper Fifth Avenue, along with the Duke, Payne Whitney, and Cook houses. Stylistically it is a Renaissance building with Gothic ornament, a sibling of the Felix Warburg house by the same architect at 1109.

79th

980 - Apartment House - P. Resnick & H. F. Green, 1968

985 - Apartment House - Wechsler & Schimenti, 1967

Destroyed to make way for this twin high-rise were two neo-Gothic mansions built by Rose & Stone in 1888 for Isaac Brokaw, nicely balancing the Stuyvesant mansion across 79th Street.

988 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

Splendid, subtle ornamentation.

80th

990 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1927

Like a slice cut from a larger building, three bays of bowed front on Fifth, eleven bays running down 80th Street. Here was once a town house built for the Woolworths in 1901 by C. P. H. Gilbert.

991 - Town House (American-Irish Historical Society, Inc.) - Turner & Kilian, 1900

A rare survivor. Built by the steel magnate William Ellis Corey, it was left to the present occupants by his son in 1940.

993 - Apartment House - Emery Roth, 1929

One of the earlier efforts by this indefatigable outfit. Born in Czechoslovakia in 1871, Emery Roth worked for the firm of Burnham & Root in Chicago and later for Richard Morris Hunt in New York before forming his own firm in 1902. It remained just “Emery Roth” until 1938, when it became “Emery Roth & Sons.” The firm's output has been enormous.

995 - The Stanhope - Rosario Candela, 1925

The only hotel on the Avenue north of the Sherry-Netherland and The Pierre, it also boasts the only sidewalk café--ideally positioned directly across from the Metropolitan Museum. This still-elegant small hotel was one of the first multi-storied buildings along the Avenue to have an upper façade of brick, not masonry.

81st

998 - Apartment House - McKim, Mead & White, 1910

A milestone, a trail-blazer, a stand-out; here's where the second wave began, the shift from private town house to apartment house, and yet it was late in the career of this architectural firm that this building was finished: White was murdered in 1906, and McKim died in 1909. Whoever was responsible did his job so well in terms of inner layout and outer design that both Carpenter and Candela took inspiration from this building. It set the tone for the multiple dwelling on upper Fifth Avenue for years thereafter, and it is still most elegantly habitable today.

1001 - Apartment House - Philip Birnbaum, 1972; Johnson - Burgee, 1978

By the time a group of developers (Kalikow) had razed several prize mansions and erected this high-rise, the public awareness of architectural values and acceptability was so strong that a hue and cry went up against so jarring a façade appearing alongside 998 and opposite the Met. Philip Johnson was called in to make things right, and his solution was a modern masonry cladding with tubular horizontal moldings that endeavor to tie it in with its neighbors, plus a false front pylon attic. Compare this with Ulrich Franzen's solution to a similar problem one mile to the south, at 800.

1009 - Mansion - A. M. Welch, 1898

Built on speculation by developers Hall & Hall, this limestone and brick house, narrow on the Avenue, long on the side street, was soon snapped up by the Duke family (see 1 E. 78th) and remained in their hands as a town house for a great many years until it was split up recently into a handful of apartments.

82nd

1010 - Apartment House - Fred F. French, 1924

Designed as well as constructed by this famous and venerable New York real estate firm (they developed both Knickerbocker Village and Tudor City in Manhattan), this building has a squareness and solidity that seem to express the essence of “apartment house.”

1014 - Town House (Goethe House) - Welch, Smith & Provot, 1906

The same Welch that did 1009. Today sandwiched between taller and larger neighbors, this five-story town house with dormered mansard and elegant detailing was once one of a pair. Built for stockbroker James F. A. Clark, today it is owned by the Federal Republic of Germany, who use it as a cultural center, with library and occasional exhibits open to the public.

1016 - Apartment House - J. B. Peterkin, 1928

A subtly ornate façade above a rusticated base.

83rd

1020 - Apartment House - Warren & Wetmore, 1924

The handsome lower façade consists of four two-story arches on Fifth Avenue and six on 83rd street, each with scroll keystones and projecting eyebrow sills above. The unusual fenestration of the upper façade (three normal-height windows every three floors on the right, two very tall windows three across every three floors on the left) is caused by the ingenious internal layout. The lower of every three floors is a duplex with a one-and-a-half story living room. Above that is a one-story apartment with a sunken living room.

1025 - Canopied Entry - Raymond Loewy - William Smith, Inc., 1955

A fine first-wave town house, owned by Frederick W. Vanderbilt (who also built the Vanderbilt mansion on the Hudson near Hyde Park), was demolished to create access to two side-street high-rises (by rights 51 E. 83rd and 70 E. 84th, designed by Hyman I. Feldman), thus giving their tenants a Fifth Avenue address. Would that the developer had at least done something more along the lines of Harry Helmsley's use of the superb Villard Houses which serve as the entrance to his high-rise Palace Hotel on Madison Avenue.

1026 - Town House - Van Vleck & Goldsmith, 1903

1027 - Town House - Van Vleck & Goldsmith, 1903

1028 - Town House - C. P. H. Gilbert, 1902

The good news after the bad: These three fine Beaux-Arts façades have been consolidated to become part of the Marymount School of New York, and thus, we can hope, rescued forever. They were formerly owned by three old New York families: Burden, Pratt, and Milbank.

84th

1030 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

Right out of his top drawer.

1033 - Town House - S. D. Hatch, 1889; remodeled Hoppin & Koen, 1912

Another first-wave town house presently dwarfed by its neighbors, this two-bay five-story eclectic mansion was sold to the Iranian Government in 1966 and is the residence of their ambassador to the U. N.

1035 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

Another first-rate effort, on a par with 1030. Below 86th Street, the second-wave apartment houses tend to be completely stone-clad; above 86th they tend to have a one- to four-story stone base with everything above that (except the ornament) of brick. This building, with limestone base and buff brick above, marks the beginning of the transition.

85th

1040 - Apartment House - Rosario Candela, 1929

A super-posh blockbuster of Candela's, larger and taller (seventeen floors) than most of his others. The façade is simple but suitably massive. Note the face masks at the fifth floor. Many celebrities dwell within.

1045 - Apartment House - H. Ginsberg, 1965

Quite a narrow frontage (forty-four feet) for an apartment house, with the only glass curtain wall on upper Fifth Avenue.

1048 - Mansion (Yivo Institute for Jewish Research) - Carrère & Hastings, 1914

Presently occupied by the Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, this Louis XIII refugee from Paris's Place des Vosges was originally built for socially prominent William Starr Miller. It was later bought and lived in by the widow of Cornelius Vanderbilt III from 1949 to 1953, after she had sold the family mansion at 52nd Street. The house is a well-preserved masterpiece inside and out, and may be visited by the general public.

86th

1050 - Apartment House - Wechsler & Schimenti, 1958

1056 - Apartment House - G. F. Pelham, 1950

87th

1060 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1927

Once the site of Henry Phipps's residence, designed by Trowbridge & Livingston. The demolition and subsequent erection of this multiple dwelling was financed by, of all people, the Henry Phipps Estate. Phipps came from Pittsburgh and made his money in steel, along with Carnegie and Frick. He invested that money in real estate and sponsored several housing projects for the working poor.

1067 - Apartment House - C. P. H. Gilbert, 1915

One of the Avenue's oldest sizable buildings. Gilbert, a consummate eclectic architect, did not design many apartment houses; his forte was the elaborate town house (see 2 E. 79th, 1 E. 91st, and 1109).

2 E. 88th - Apartment House - Pleasants, Pennington & Lewis, 1929

These three second-wave apartment houses (1060, 1067, and 2 E. 88th) share a whole block front, as well as an elegant mood. The details and the textures vary, but there's an underlying architectural harmony.

88th

1070-6 - Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum - Frank Lloyd Wright, 1959

The only major work in New York City by the master architect from the Midwest, this cream stucco mass with its spiral “silo” may startle somewhat and jar with its more traditional neighbors on the exterior, but within is one of the city's most exciting interior spaces.

89th

1080 - Apartment House - Wechsler & Schimenti, 1960

1083 - Town House (National Academy of Design) - Turner & Kilian, 1901

Founded originally by Samuel F. B. Morse, the Academy is a conservative organization whose members include architects, painters, and graphic designers. There are continuous exhibitions of great variety open to the public. This charming town house, donated in 1940 by Archer M. Huntington, wraps around 1080 to join another town house and studio building on 88th Street.

2 E. 90th - Church of the Heavenly Rest - Mayers, Murray & Phillip, 1929

These three architects formed the successor firm to Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, the brilliant designer of four of New York's loveliest churches: St. Bartholomew's, St. Thomas's, St. Vincent Ferrer, and the Chapel of the Intercession, at Broadway & 155th Street. Since Goodhue died in 1924 and construction of this church began in 1927, and since the preparatory design stage of large ecclesiastical structures usually takes a good many years, it is possible, and I trust safe, to assume that Goodhue was in on the basic conception, if not the details, of this fine all-limestone neo-Gothic church. At any rate, the results are splendid, with elegant Art Deco ornamental sculpture inside and out. The church currently sponsors outstanding jazz concerts in addition to its regular Episcopalian services.

90th

2 E. 91st - Mansion (Cooper-Hewitt Museum) - Babb, Cook & Willard, 1901

Built for Pittsburgh steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie when the Avenue this far north was still the boonies. In fact, squatters had to be evicted and their shanties cleared away before construction on the house could get under way. This large mansion is beautifully sited on a full-block frontage, with a handsome fence enclosing the free-standing house and its spacious grounds on all sides. How intriguing that two out-of-town partners in steel (Carnegie and Frick) should build mansions on block-wide sites exactly one mile apart, and that both should survive as museums, with their houses and grounds intact. The Cooper-Hewitt is The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Design; it mounts constantly-changing exhibitions from the permanent collection and from other sources.

91st

1 E. 91st - Mansion (Convent of the Sacred Heart) - C. P. H. Gilbert & J. A. Stenhouse, 1918

This masterpiece of an Italian-Renaissance, London-clubhouse palazzo was created for Otto Kahn by C. P. H. Gilbert, with a little help from an unknown British architect. Clad in beautiful imported French limestone and with a scheme of ornamentation surprisingly sober for Gilbert, this huge mansion, with built-in carriage entrance on the side street, was Kahn's second commissioned residence; the first was (and still is) at 8 E. 68th Street, built for him eighteen years earlier by John H. Duncan, the architect of Grant's Tomb.

1107 - Apartment House - W. K. Rouse & L. A. Goldstone, 1925

This enormous building is memorable for the fifty-four-room triplex apartment assembled therein by Post-Toasties heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post during the 1920s. The only outward evidence of this regal suite is the great Palladian window visible on the twelfth floor, probably in one of her larger living rooms. With this apartment, we have the perfect example of the lavish town house transplanted to the lavish apartment house. The building's interior porte-cochère around on 92nd Street echoes the one in the Otto Kahn house one block south at 91st Street.

92nd

1109 - Mansion (The Jewish Museum) - C. P. H. Gilbert, 1908; addition, Samuel Glazer, 1963

The main house was built for Felix M. Warburg, whose widow, Frieda Schiff Warburg, sold it for one dollar to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in 1940. The Seminary in turn made it over into the splendid Jewish Museum, a very active one with an ambitious program of ever-changing public exhibits. The house itself, one of Gilbert's most picturesque efforts, is in the late French Gothic style of the Loire Valley, with generous Renaissance embellishments.

1115 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

93rd

1120 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1924

A pair of nearly identical twins stand alongside each other on opposite corners of the side street. Carpenter did this again farther north, at 98th Street. Here the effect is surprisingly pleasing and the buildings charming. The unusual spacing of the windows creates a nice horizontal rhythm. Notice that the lower floors of 1115 have rounded windows, while those of 1120 are flat-topped.

1125 - Apartment House - Emery Roth, 1925

A very early work by Roth, and very respectful of the neighboring Carpenter opus. The two buildings are the same height (fourteen stories), but while 1120 is a large fourteen bays wide, Roth's 1125 has only five bays.

94th

1130 - Mansion (International Center of Photography) - Delano & Aldrich, 1913

Another Delano & Aldrich neo-Georgian beauty, built for Willard Straight, a financier, diplomat, and publicist from upstate who married Whitney money and helped found the New Republic magazine. After several changes of hands, the house became headquarters for the National Audubon Society in 1952. More recently it has been turned into a museum: the International Center of Photography, which offers excellent shows for the public. The red brick mansion with white stone trim is of a comfortable residential scale and has the unusual decorative feature of the round bulls-eye windows on the fourth floor.

NOTE: The following ten apartment houses are all of the same period: 1920-1927, the high point of the second wave. The buildings are pretty much all of a piece: They are restrained, refined, dignified, affluent blow-ups of neo-Renaissance Italianate palaces; their bases are masonry-clad and their upper stories brick with stone trim. Though they are remarkably similar, they are never boring. At nearly uniform height (twelve to fifteen stories), they hold the street line beautifully and comfortably encompass the two shorties: 1143 at seven and 1160 at only six stories. Thanks to the subdued yet variegated ornament of fluted pilasters, escutcheons, spiral columns, floral moldings, carved window surrounds, and cornices, they successfully avoid monotony.

1133 - Apartment House - Emery Roth, 1927

1136 - Apartment House - G. F. Pelham, 1924

95th

1140 - Apartment House - Fred F. French, 1921

1143 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1923

A narrow (four-bay wide) and low (seven floors high) midget squeezed between two giants. Perhaps the site was that of a town house holdout when 1140 and 1148 were being assembled and built. If so, the strategy failed, for this apartment house was built a scant two years later.

1148 - Apartment House - W. B. Chambers, 1920

96th

1150 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1923

1158 - Apartment House - C. H. Crane & K. Franzheim, 1924

97th

1160 - Apartment House - Fred F. French, 1922

1165 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

George Plimpton grew up in this building.

98th

1170 - Apartment House - J. E. R. Carpenter, 1925

These last two are Carpenter's other set of near-identical twins. The entrances, in this case, face each other across the side street, which somehow emphasizes the feeling of twinness.

99th

100th Street and Fifth Avenue - Mount Sinai Hospital - Arnold W. Brunner, 1904; Kahn & Jacobs, 1952; Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 1976

This huge and venerable hospital stretches from just north of 98th Street to 101st, swallowing the intervening cross streets. 1176 Fifth Avenue is The Klingenstein Pavilion, 1184 is The Guggenheim Pavilion, and 1200 and 1212 are doctors offices. The Housman Pavilion is at 1 E. 100th Street. The quality of the architecture is not very exciting except, perhaps, for the gigantic rusted-steel Annenberg Building of 1976, set back in a courtyard reachable by Gustave L. Levy Place, and dominating everything for miles around. A new complex of buildings designed by I.M. Pei will soon replace the leftmost buildings shown in the poster photos.

101st

1200 - Apartment House - Emery Roth, 1928

1212 - Apartment House - George & Edward Blum, 1925

102nd

1215 - Apartment House - Schultze & Weaver, 1928

These are the architects we started out with at 59th Street and the Sherry-Netherland Hotel. Noted primarily for their posh hotels, here they essay one of their rare ventures into the apartment house field, and it's a successful one. Within was Louis Brisbane's fabulous multiplex apartment, specially designed by Carrère & Hastings. The fine neo-Romanesque exterior, anticipated by the triple-arched entry and fourth-floor window surrounds of 1212, boasts a handsome carved entrance, fifth-floor balustrade, and smooth limestone cladding that tie in with:

2 E. 103rd - New York Academy of Medicine - York & Sawyer, 1926

The random light and dark stone work of this Byzantine-Romanesque palace give it a Pisan look. The architects are best known for their banks (Bowery Savings on 42nd Street, Federal Reserve, and many others), and yet they seem perfectly comfortable and somewhat stylish here. The Academy was formed in 1847 to raise the standards of the city's medical profession. Its library (open to the public) unexpectedly contains what is described as the world's largest collection of cook books, bequeathed by Dr. Margaret Barclay Wilson.

103rd

1220-7 - Museum of the City of New York - Joseph H. Freedlander, 1932

The museum's first home was Gracie Mansion before that charming house was taken over as a residence for the mayor of New York City. In 1932, the museum moved to this neo-Georgian leviathan that could easily be a taken for a suburban high school. It was built with funds raised by private subscription on land provided by the city. All this communal effort was well worthwhile, for it offers a delightful array of exhibits.

104th

1230 - El Museo del Barrio - Maynicke & Franke, 1925

Built in the 1920s to house the Heckscher Foundation for Children (providing recreation for underprivileged children) and the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (engaged in the care and education of abused and delinquent children), this mammoth, block-filling neo-Georgian building is now a museum devoted to Hispanic-American culture.

105th

1249 - The Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center - York & Sawyer, 1921

Formerly Flower Fifth Avenue Hospital. Here the noted bank architects are in their neo-monastery mood, with a quadropartite building crowned by a round pavilion with burnt-tile roof.

106th

1250 - Apartment Complex - Gruzen & Partners, 1976

These poured-concrete and brick buildings carry the title of Fifth Avenue Lakeview Apartments.

107th

1255 - Co-op Apartment House - ?

The photo on the poster shows the building that used to be on this site: the Home & Hospital of the Daughters of Israel, L. A. Abramson, 1925, which was empty at the time (June, 1983).

NOTE: This is as far as the poster photos go.

1265 - Parking lot

108th

1270 - Co-op housing - H. H. & C. Lilien, 1958

1274 - Apartment House - G. G. Miller, 1924

This unpretentious tenement has fire escapes on the front, recalling older neighborhoods. It is interesting that Fiorello H. LaGuardia lived here during the 1930s while he was mayor. It was from his apartment here that he read the funnies over the radio during a newspaper strike.

109th

1280 - Commercial Building - Fred F. French, 1922

Built for Edith Cram in the 1920s, this one-story building, with two ticket windows facing Fifth Avenue, was used as a TV studio in the 1950s. It was home to early episodes of “I Love Lucy”. It now houses the Youth Action Program.

Frawley Circle

This corner of the block contains one fourth of Frawley Circle, and is taken up by an abandoned filling station.

110th

Across 110th Street, and forming a fitting terminus to upper Fifth Avenue as well as a gateway to Harlem, rise the twin thirty-five-story octagonal towers of the Schomburg Plaza Apartment complex, the 1975 work of Gruzen & Partners.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Scitex America Corp. for their collaboration on this project,

Steve Marvin, who wrote the booklet,

Nicola Wood, who painted the title of the poster,

Gayle Rosen, who did the compositing on the Scitex Response System,

Trish Beall, who edited The Making of the Poster,

Sarah Blackburn, who edited Steve Marvin's prose,

Timothy Guzley, who did booklet fact checking (he was referred by The New Yorker),

Nick Haddon, who got the project adopted within Scitex,

Paul Thiel, who saw it through within Scitex,

and I would like to thank the following other people who provided help, work, support, or encouragement: Zsoka Barkacs, Pam Becker, Tom Barron, Homer Dunn, Daniel Gilbert, John Gilbert, Skip Gilbrech, Ron Globus, Ilan Hagari, Rick Kiessig, Susan Labella, John Lilly, Megan McCarthy, Nancy Murray, John Ost, Margerie Pearson, Robert Richer, Bob Savini, Craig Schwartz, Libby Shaw, Cathy Sherman, Janine Simmons, Richard Thies, George Turnbull, Jim Wall, Elliot Willensky, and Lynn Yost.

--David Yost [updated 8/97]

Bibliography

“Fifth Avenue and Central Park Building-Structure Inventory”

by Alexandra Cushing Howard

commissioned by the Division for Historic Preservation, 1975

New York State Parks and Recreation,

Albany, NY

in the files of the Landmarks Preservation Commission of the City of New York

225 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

Fifth Avenue

by Theodore James, Jr.

Walker & Company, 1971

New York

(NY Hist. Soc. library)

The Select Register of Apartment House Plans

New York Select Realty Register, Inc. (date unknown)

Pease and Elliman's Catalogue of Eastside of New York Apartment Plans

by A.G. Blaisdell

New York, 1922

(NY Historical Society library)

A.I.A. Guide to New York City

by Norval White and Elliot Willensky

Collier Books, 1978

New York

ISBN 0-02-626580-X

LaurelArts, David Arthur Yost; Yost.com, All Rights Reserved.

http://Yost.com/Art/FifthAvenue/FifthAvenue-booklet.html - this page

1997-06-14 Created

2001-08-26 Modified

2010-10-25 Added Steve Marvin pic and movie link

2014-05-17 Added George Plimpton reference

2014-06-09 Added Huguette Clark reference

2020-05-24 Corrected Széchenyi